ALICE KER (1853-1943)

Alice Jane Shannan Stewart Ker was born on 2 December 1853 at Deskford, Cullen, Banffshire. She was the eldest of nine children born to Reverend William Turnbull Ker (d. 1885) and Margaret Millar Stevenson (d. 1900). Her maternal grandfather was James Cochran Stevenson, manager of Jarrow Chemical Company in South Shields, a business built up by his father, James Stevenson, who was married to Jane Stewart née Shannan. Margaret was one of eleven children, the eldest of the six daughters. Three of Margaret’s sisters, Elisa, Flora and Louisa, lived in Edinburgh and were involved in social and political questions of the day.

Becoming a doctor

In 1872, Alice began her studies at Edinburgh University which included classes on physiology and anatomy. In the following year, the university prohibited women from taking medical degrees. Alice then went to Dublin to take her exams at the King and Queen’s College of Physicians in Ireland, continuing her studies at Berne in Switzerland paid for by her Aunt Flora Stevenson. In 1879, Alice’s name was added to the medical register, the 13th woman to become a doctor.

We hold a small collection of items in The Women’s Library relating to Alice’s career. In 1884, Alice Ker gave two lectures to women – the first on infancy and childhood and the second on girlhood – which were part of the Manchester Domestic Economy Classes. The lectures were later published as pamphlets.[i]

Becoming a doctor

In 1872, Alice began her studies at Edinburgh University which included classes on physiology and anatomy. In the following year, the university prohibited women from taking medical degrees. Alice then went to Dublin to take her exams at the King and Queen’s College of Physicians in Ireland, continuing her studies at Berne in Switzerland paid for by her Aunt Flora Stevenson. In 1879, Alice’s name was added to the medical register, the 13th woman to become a doctor.

We hold a small collection of items in The Women’s Library relating to Alice’s career. In 1884, Alice Ker gave two lectures to women – the first on infancy and childhood and the second on girlhood – which were part of the Manchester Domestic Economy Classes. The lectures were later published as pamphlets.[i]

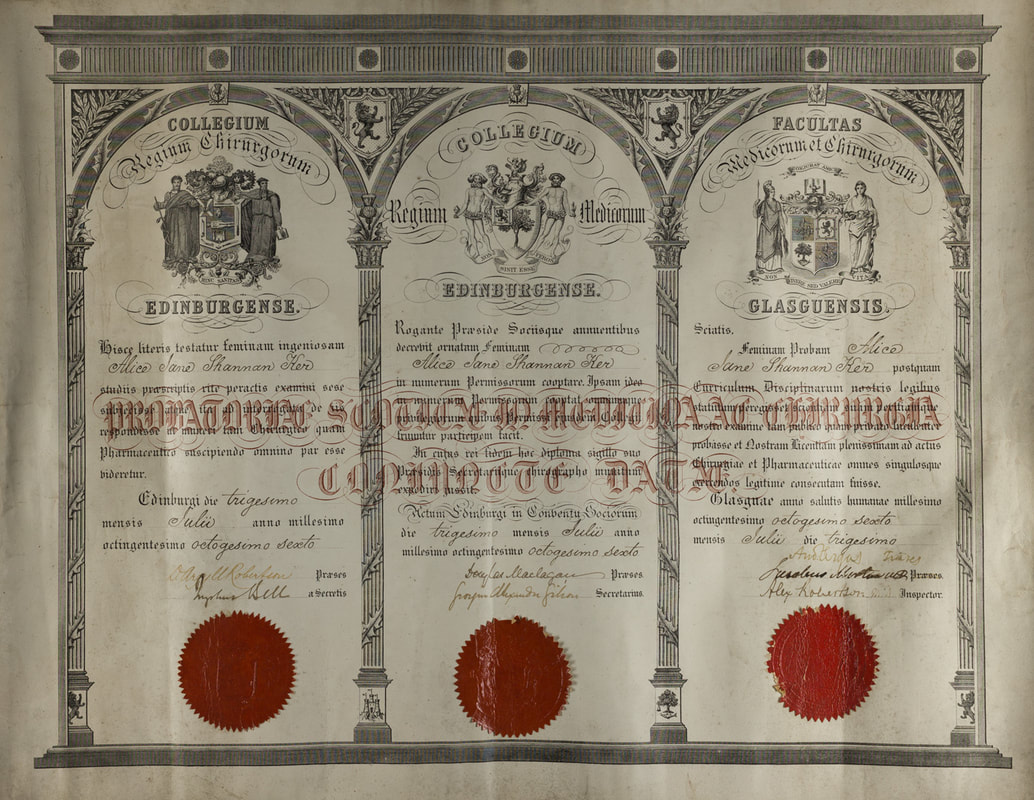

In 1886, Alice was awarded a Triple Qualification certificate from three Scottish Colleges.[ii] The General Medical Council approved this non-University route to a medical degree. It was not until 1896 that Edinburgh University allowed women to graduate with medical degrees.

|

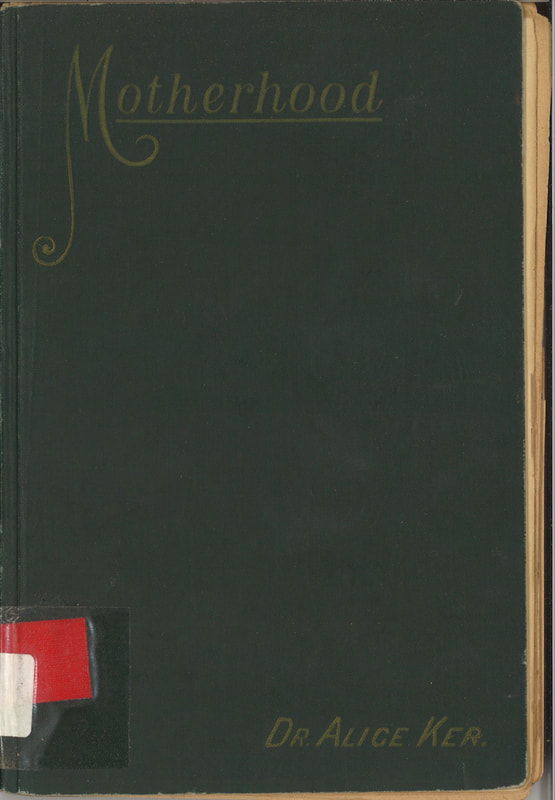

By 1891 Alice was now an Honorary Medical Officer in the Wirral Hospital for Sick Children and to the Birkenhead Lying-In Hospital, having moved to Liverpool after marrying Edward Ker, a shipping merchant, in 1888. She also published a book entitled Motherhood: a book for every woman with a second edition published in 1896.[iii] In the preface, Alice wrote: “the book is written, not to give amusement nor to excite a passing interest, but to help those who earnestly desire to live the highest life that is possible for them.” It was a health manual written in plain language giving advice on marriage, pregnancy, the care of babies and female adolescents. The final chapter considers the menopause and an appendix on what to wear during the ‘monthly indisposition’.

In 1898, Alice was one of 73 women doctors to sign a letter to the Secretary of State for India about the measures adopted for dealing with sexual transmitted diseases in the Indian Army.[iv] Amongst the other signatories were Elsie Inglis, Alice and Agnes McLaren, Mary Baird Hannay and Grace Ross Cadell. Involvement in the Suffrage Movement From the digitised copies of suffrage journals, it is easier to chart Alice’s involvement in the suffrage movement. Searching LSE’s digital library, Alice was active in Leeds when she lived there in the early 1880s. On 2 October 1885, she was part of a deputation representing women householders of Leeds, with a petition of 7,000, and put the case for them to the Liberal MP Arthur Rucker asking him to favour women householders getting the vote. In 1887, Alice lived at 10 Doane Terrace, Edinburgh, and held a drawing room meeting about women getting the vote because they pay taxes and rates. The motion was seconded by her aunt Louisa Stevenson. On moving to Birkenhead, Alice was involved with the Birkenhead Women’s Suffrage Society and spoke at public meetings such as the one on 28 September in 1908. |

Around this time, Alice changed allegiance from suffragist to suffragette, which can be followed in a series of letters from Constance Lytton to Alice held in The Women’s Library. Constance always referred to Alice as “Dear Dr Ker” and in a letter, dated 13 November 1909, she rejoiced that Alice was now “one of us [WSPU]. We really are not wicked.”[v] On 27 February 1912, Alice was in London to meet Constance and Annie Besant about a meeting at the Royal Albert Hall[vi] and then on 4 March, Constance wrote to Alice’s daughter, Margaret:

“Your mother has been perfectly splendid! You will know by the time you get this that she ‘smashed’ at Harrod’s Brompton Road and was arrested with two others….”[vii]

Alice had taken part in the mass window smashing campaign in London in March 1912. During Alice’s remand, Constance wrote encouraging letters to Margaret and Alice’s younger daughter, Mary.

On 13 March, Constance began:

“Your mother was absolutely magnificent at Westminster (Rochester Police court) yesterday. The magistrate was contemptuous and cross, in fact insulting. She cross-examined the witness a shop salesman as if she had been an expert lawyer. He gave such conflicting evidence.”[viii]

And again on 17 March: “Everyone loves and admires her who sees her. Did you see the reference to her in Mrs Besant’s letter to The Times?”[ix]

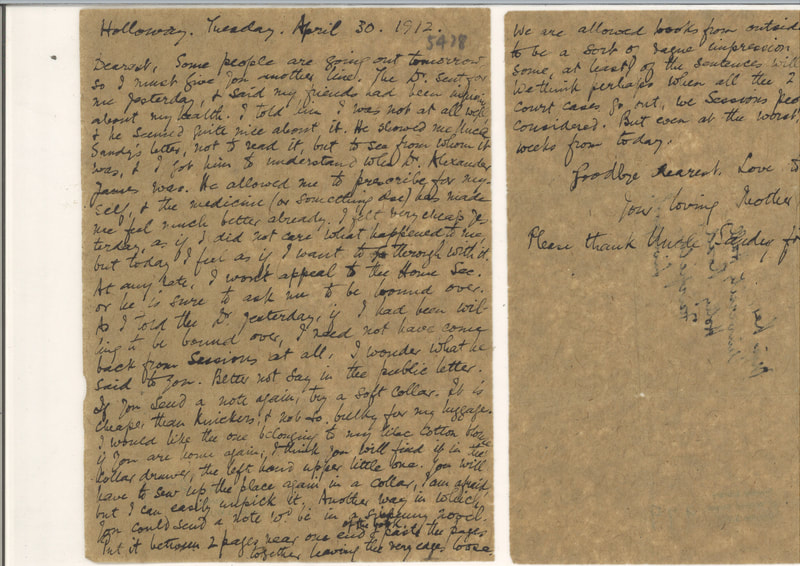

During this long remand period, Alice wrote many letters (all in The Women’s Library) to her daughters asking them to be strong and to send her things including a half-worked embroidered tea-cloth with linen threads and a book of embroidery stitches.[x] Alice was sentenced on 28 March 1912 to three months imprisonment in Holloway. She was 59. Letter writing was more restrictive after sentencing but Alice managed to smuggle out this letter written on toilet paper.[xi] Alice went on hunger-strike but was not force-fed. She was released on 3 May.

“Your mother has been perfectly splendid! You will know by the time you get this that she ‘smashed’ at Harrod’s Brompton Road and was arrested with two others….”[vii]

Alice had taken part in the mass window smashing campaign in London in March 1912. During Alice’s remand, Constance wrote encouraging letters to Margaret and Alice’s younger daughter, Mary.

On 13 March, Constance began:

“Your mother was absolutely magnificent at Westminster (Rochester Police court) yesterday. The magistrate was contemptuous and cross, in fact insulting. She cross-examined the witness a shop salesman as if she had been an expert lawyer. He gave such conflicting evidence.”[viii]

And again on 17 March: “Everyone loves and admires her who sees her. Did you see the reference to her in Mrs Besant’s letter to The Times?”[ix]

During this long remand period, Alice wrote many letters (all in The Women’s Library) to her daughters asking them to be strong and to send her things including a half-worked embroidered tea-cloth with linen threads and a book of embroidery stitches.[x] Alice was sentenced on 28 March 1912 to three months imprisonment in Holloway. She was 59. Letter writing was more restrictive after sentencing but Alice managed to smuggle out this letter written on toilet paper.[xi] Alice went on hunger-strike but was not force-fed. She was released on 3 May.

Alice continued to be active in the suffrage movement and beyond. The Suffragette in January 1914 gave thanks to her in for keeping the offices open in Liverpool during the Christmas holidays. Around 1916, Alice moved to London and, in 1932, she was secretary of the Hendon Women’s Citizens’ Council and living at 58 Denman Drive NW11. Alice died on 20 March 1943.

Further reading and resources:

Krista Cowman, ‘Alice Jane Shannan Stewart Ker’ Oxford of National Biography (2004)

Elizabeth Crawford 'The Women's Suffrage Movement: A reference guide 1866-1928'.

Gillian Murphy (2020) “The prison letters of Alice Ker and Mary Ellen Taylor: suffragettes and mothers”, Women's History Review, 29:6, 955-969, DOI: 10.1080/09612025.2020.1745402

LSE Library archive catalogue search for “Alice Ker” in ‘anytext’ field https://archives.lse.ac.uk/

LSE Digital Library for suffrage journals https://digital.library.lse.ac.uk/

LSE Library Flickr site https://www.flickr.com/photos/lselibrary/ and link to Alice’s embroidery https://flic.kr/p/27DhMoJ

[i] Alice Ker, Infancy and Childhood (Manchester, 1884) and Girlhood (Manchester, 1884).

[ii] The Women’s Library at LSE, 10/54/132.

[iii] Alice Ker, Motherhood: a book for every woman, 2nd edition, (London: John Heywood, 1896).

[iv] Memorial of medical women address to the Secretary of State for India on the subject of the measures recently adopted for dealing with Contagious Disease in the Indian Army, February 1, 1898, reprinted by Ladies’ National Association for the Abolition of State Regulation of Vice, 1912.

[v] The Women’s Library at LSE, 9/21/05.

[vi] The Women’s Library at LSE, 9/21/27.

[vii] The Women’s Library at LSE, 9/21/28.

[viii] The Women’s Library at LSE, 9/21/29.

[ix] The Women’s Library at LSE, 9/21/30.

[x] The Women’s Library at LSE, 9/29/62 for the letter and TWL.2012.26 for the embroidery.

[xi] The Women’s Library at LSE, 9/29/79.

Further reading and resources:

Krista Cowman, ‘Alice Jane Shannan Stewart Ker’ Oxford of National Biography (2004)

Elizabeth Crawford 'The Women's Suffrage Movement: A reference guide 1866-1928'.

Gillian Murphy (2020) “The prison letters of Alice Ker and Mary Ellen Taylor: suffragettes and mothers”, Women's History Review, 29:6, 955-969, DOI: 10.1080/09612025.2020.1745402

LSE Library archive catalogue search for “Alice Ker” in ‘anytext’ field https://archives.lse.ac.uk/

LSE Digital Library for suffrage journals https://digital.library.lse.ac.uk/

LSE Library Flickr site https://www.flickr.com/photos/lselibrary/ and link to Alice’s embroidery https://flic.kr/p/27DhMoJ

[i] Alice Ker, Infancy and Childhood (Manchester, 1884) and Girlhood (Manchester, 1884).

[ii] The Women’s Library at LSE, 10/54/132.

[iii] Alice Ker, Motherhood: a book for every woman, 2nd edition, (London: John Heywood, 1896).

[iv] Memorial of medical women address to the Secretary of State for India on the subject of the measures recently adopted for dealing with Contagious Disease in the Indian Army, February 1, 1898, reprinted by Ladies’ National Association for the Abolition of State Regulation of Vice, 1912.

[v] The Women’s Library at LSE, 9/21/05.

[vi] The Women’s Library at LSE, 9/21/27.

[vii] The Women’s Library at LSE, 9/21/28.

[viii] The Women’s Library at LSE, 9/21/29.

[ix] The Women’s Library at LSE, 9/21/30.

[x] The Women’s Library at LSE, 9/29/62 for the letter and TWL.2012.26 for the embroidery.

[xi] The Women’s Library at LSE, 9/29/79.