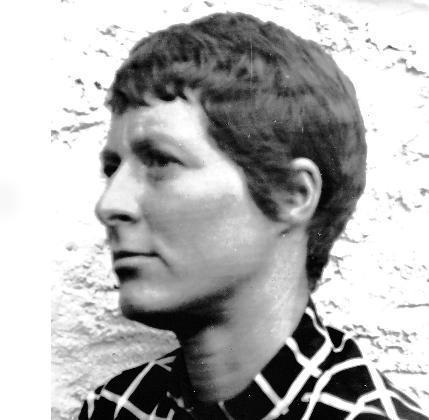

BARBARA BALMER (1929-2017)

The artist and teacher, Barbara Balmer RSA, RSW, RGI was born in Birmingham and came to Scotland in the 1950s to study at Edinburgh College of Art. She remained in Scotland until 1980, and as with Joan Eardley she has been embraced as a Scottish painter. Her work is to be found in the collections of major public galleries, including her self-portrait in the National Gallery of Scotland, Self Portrait on a Frosty Friday morning (1995). The portrait of her friend Richard Demarco is displayed in the Scottish National Portrait Gallery in Edinburgh. She is represented in university, civic and private collections with Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother one of many acolytes. Balmer had 24 solo shows and a touring retrospective. In the 1970s, Balmer’s work was brought to the attention of a new generation. Virago Press adroitly matched Balmer’s work with their Modern Classics series including titles by Angela Carter, Sylvia Ashton-Warner and Rosamund Lehmann. Balmer’s An American in Paris graces an early dust jacket of The Magic Toyshop. Prior to her death in 2017, the Fine Art Society showed her paintings alongside another formidable living Scottish artist, John Byrne. Despite these accolades, she merits no mention in Macdonald’s Scottish Art (2000).

Like all artists, Barbara experimented with style, but her signature formed early in her career. She drew her influences from the early Italian primatives, Stanley Spencer and Giorgio Morandi ‘but maintains that her first ever visit to Italy in 1973 was the most inspirational.’ (Rendezvous Gallery Invitation, 2016). Annual trips to Italy continued to inform her body of work. The art critic for Scotland on Sunday opined: ‘Pictorialist, stylist, classisist, modernist. She is all of these things and more. Instantly identifiable at fifty yards.’ (Gordon Smith 1996)

Barbara lived at No. 7 Park Road with her husband the graphic designer, George Mackie. Her subjects were drawn from friends and families, and local scenes. Many of her still life paintings feature aspects of the house and its contents: astragal windows and artful arrays of objets from black lacquer tables, kettles, jugs and geraniums (Lacquer Table 1959, Bedroom Window 1966). During this period, her milieu may have been local but like her friend Nan Shepherd ‘she was a localist of the best kind: she came to know her chosen place closely, but that closeness served to intensify rather than to limit her vision.’ (Macfarlane in his Introduction to The Living Mountain, 2011). Her painting of Nan Shepherd’s Sun Porch (date unknown) is commanding in keeping with the cultural stature of its diminutive subject.

Barbara Balmer donated a painting (no name 1964) to St Margaret’s School for Girls in Aberdeen where her daughters, Ruth and Rachel, were pupils in the 1960s. The painting is a verdant landscape taking in the South Deeside vista. The blue of the River Dee is central to the composition. A black corvid, a sense of disquiet, flies low over furrowed fields and out of the frame.

Barbara exuded a certain ‘band-box vivacity’ (Ritchie, 1983) and this quality was not lost on her students and colleagues at Gray’s School of Art where she taught from 1970 to 1980. She also taught Laban Movement and Dance in the Cowdray Hall. Barbara used a marionette in figurative work and this jointed doll became a subject in a series of Watercolours. Blindfolded and bound with black ties these studies show the same precision and a certain sense of disquiet as evident in her natural works (Lay Person 1, The Manoeuvre, Voyage of the Creeper).

Barbara made a strong impression on those whom she met and maintained long term and long-distance friendships with the Richard Demarco, artist and original promoter of the arts at the Edinburgh International Festival and Fringe who was her contemporary at Edinburgh College of Art in the 1940s. It was Demarco who penned her obituary for The Herald. Notoriously discerning, and internationally focused, Demarco posits that Balmer’s ‘unswerving devotion to her art resulted in paintings of extraordinarily beautiful refinement, expressing her love for the visual world … Her particular art must be viewed as belonging to the great and enduring tradition associated with the latest manifestations of European painting in this age of modern art’. That Balmer’s artistic legacy was undervalued in her lifetime, especially as a female artist, could simply be ‘ever thus’. Now seems a good time to revisit her oeuvre and cultural place in the North-east of Scotland, in Britain and beyond.

Entry written by Nicola Furrie.

Like all artists, Barbara experimented with style, but her signature formed early in her career. She drew her influences from the early Italian primatives, Stanley Spencer and Giorgio Morandi ‘but maintains that her first ever visit to Italy in 1973 was the most inspirational.’ (Rendezvous Gallery Invitation, 2016). Annual trips to Italy continued to inform her body of work. The art critic for Scotland on Sunday opined: ‘Pictorialist, stylist, classisist, modernist. She is all of these things and more. Instantly identifiable at fifty yards.’ (Gordon Smith 1996)

Barbara lived at No. 7 Park Road with her husband the graphic designer, George Mackie. Her subjects were drawn from friends and families, and local scenes. Many of her still life paintings feature aspects of the house and its contents: astragal windows and artful arrays of objets from black lacquer tables, kettles, jugs and geraniums (Lacquer Table 1959, Bedroom Window 1966). During this period, her milieu may have been local but like her friend Nan Shepherd ‘she was a localist of the best kind: she came to know her chosen place closely, but that closeness served to intensify rather than to limit her vision.’ (Macfarlane in his Introduction to The Living Mountain, 2011). Her painting of Nan Shepherd’s Sun Porch (date unknown) is commanding in keeping with the cultural stature of its diminutive subject.

Barbara Balmer donated a painting (no name 1964) to St Margaret’s School for Girls in Aberdeen where her daughters, Ruth and Rachel, were pupils in the 1960s. The painting is a verdant landscape taking in the South Deeside vista. The blue of the River Dee is central to the composition. A black corvid, a sense of disquiet, flies low over furrowed fields and out of the frame.

Barbara exuded a certain ‘band-box vivacity’ (Ritchie, 1983) and this quality was not lost on her students and colleagues at Gray’s School of Art where she taught from 1970 to 1980. She also taught Laban Movement and Dance in the Cowdray Hall. Barbara used a marionette in figurative work and this jointed doll became a subject in a series of Watercolours. Blindfolded and bound with black ties these studies show the same precision and a certain sense of disquiet as evident in her natural works (Lay Person 1, The Manoeuvre, Voyage of the Creeper).

Barbara made a strong impression on those whom she met and maintained long term and long-distance friendships with the Richard Demarco, artist and original promoter of the arts at the Edinburgh International Festival and Fringe who was her contemporary at Edinburgh College of Art in the 1940s. It was Demarco who penned her obituary for The Herald. Notoriously discerning, and internationally focused, Demarco posits that Balmer’s ‘unswerving devotion to her art resulted in paintings of extraordinarily beautiful refinement, expressing her love for the visual world … Her particular art must be viewed as belonging to the great and enduring tradition associated with the latest manifestations of European painting in this age of modern art’. That Balmer’s artistic legacy was undervalued in her lifetime, especially as a female artist, could simply be ‘ever thus’. Now seems a good time to revisit her oeuvre and cultural place in the North-east of Scotland, in Britain and beyond.

Entry written by Nicola Furrie.