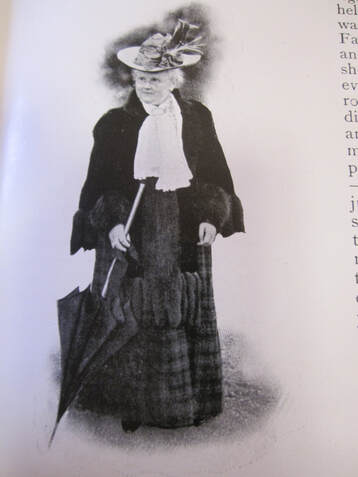

MARIAN FARQUHARSON (1846-1912)

By the end of the 19th century it was becoming increasingly clear that if women were to contribute to the science of botany – rather than remaining mere collectors or painters of plants – they needed to be able to mix with their male peers on equal terms, to learn from them, to report their own discoveries, and to make friendships. As it was, women had few personal contacts within the scientific world, thereby being further disadvantaged against men in the already unequal competition for employment.

Marian Farquharson realised that women must be able to become full members of those many scientific societies from which at the time they were excluded. Her greatest battle was with the Linnean Society, the oldest extant natural history society in the world. Ultimately, she won the argument but she was never able to enjoy the fruits of her victory.

Marian Sarah Ridley was born on 2nd July 1846 at West Meon, Hampshire, where her father was the vicar of St Thomas’ church in the parish of East Woodhay. Her grandfather was the 2nd Baronet Ridley and she was distantly related by marriage to Ishbel Hamilton-Gordon (Lady Aberdeen). Always proud, and some said arrogant, Marian also drew strength from knowing that she was a descendent of Bishop Nicholas Ridley, the Protestant Martyr. In later life, the subjects of her letters to Aberdeen newspapers ranged from opinions on free trade to those on baptismal regeneration and the historical Christ.

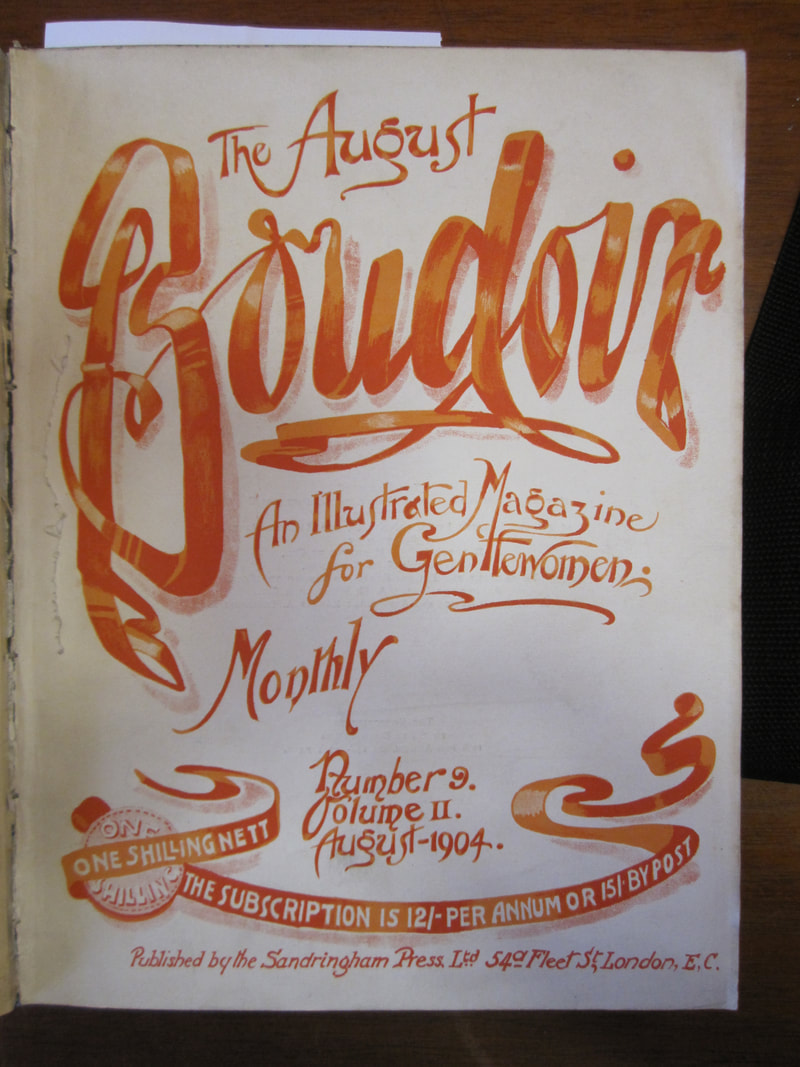

Ill health, which dogged her throughout her life, forced the young Marian to give up studying music in London. She returned home and, maybe attempting to improve her health, took up field botany, in 1881, publishing, A Pocket Guide to British Ferns. Although acknowledging help from two members of the Linnean Society’s staff, she wrote that her studies would have been aided if she had been allowed direct access to the archives of the Society.

Two years later, at age 37, she married the 60-year old Robert Francis Ogilvie Farquharson, a father of two and laird of the 4,500 acre Haughton estate at Alford, 25 miles north-west of Aberdeen. He was Deputy Lord Lieutenant of Aberdeenshire. It is not known how the couple met but they shared an interest in desmids (unicellular green algae that live in freshwater) and mosses, publishing papers describing those collected in the Alford region. Marian applied successfully to join the Royal Microscopical Society (though women fellows were barred from its meetings), thereafter signing herself ‘Mrs Farquharson of Haughton FRMS’. Alas, the marriage was only seven years old when Robert died from influenza. Haughton House passed to her step-daughter. Now in love with

Scotland, Marian moved to Meigle, Perthshire , and then to the large Italianate ‘Tillydrine House’ overlooking the river Dee and Grampian mountains.

With mounting ill health limiting her travelling, it was from a distance that Marian began her fight with the London-based, male-dominated, scientific establishment. By 1899 she was not only submitting a paper supporting the right of women to join scientific societies, a key resolution of Lady Warwick’s newly formed Agricultural Association for Women, but she was contributing a paper (in her absence, read for her by Lady Marjorie Gordon) on the subject of ‘Work for Women in the Biological Sciences’, to The International Congress of Women held in London in 26 June to 7 July. The President of the Congress was Lady Aberdeen.

Women were becoming more organised, less patient with their position in scientific society. In 1900, Marian petitioned both the Royal Society and the Linnean Society that suitably qualified women should be eligible for election for full fellowship, with no restriction on their attendance at meetings. The Royal Society consulted its lawyers and then refused her petition (it was not until 1945 that it admitted its first female fellows). The Linnean Society stalled, citing a series of procedural objections and requiring a re-submission of her petition. After two years of hard argument and lobbying, Marian achieved her goal. Opposition crumbled and The Linnean agreed revise its Charter, henceforward offering full fellowship to suitably qualified women.

Many of the male members had, however, formed a dislike of Marian. Thus, when the first group of women applied for fellowship, fifteen were admitted and Marian alone was blackballed. This was in spite of her Certificate of Recommendation being signed by the eminent politician/scientists Lords Avebury and Ripon, and the eminent academic scientists, Michael Foster, Joseph Reynolds Green, and William Carmichael McIntosh (Professor of Natural History at St. Andrews University, and a personal friend).

Marian’s name was far from popular with many male members of The Linnean, and even with some of the new elected women Fellows who had benefitted from her efforts (an exception was the geologist Maria Ogilvie Gordon, see elsewhere on this site). However, her case was finally reviewed in 1908 and she was offered a Fellowship. Her fragile health had unfortunately deteriorated further. Twice she had to ask the Linnean’s Council to postpone the date when she might attend a meeting at which she could sign the Declaration that would formalise her fellowship. She visited Nice in the hope that its gentler Mediterranean climate would restore her health. Sadly, it did not. Brave, fearless and, probably, overbearing, the women’s champion died there on 20 April 1912, a fellowship of the Linnean Society having eluded her.

Marian is buried in the Farquharson family enclosure at Alford, close to Robert and to his first wife, Sarah.

The Linnean was not the first scientific society to admit female fellows but, thanks to its prestige, its decision set an example that others were encouraged to follow.

Further Reading

Ayres, PG. 2020. Women and the Natural Sciences in Edwardian Britain. In Search of Fellowship. London: Palgrave MacMillan.

Ayres, PG. 2020. Women and the Natural Sciences in Edwardian Britain. In Search of Fellowship. London: Palgrave MacMillan.

Ayres, PG. 2022. Marian Farquharson and the Struggle for the Admission of Women Fellows. The Linnean: Special Issue No. 10. The Linnean Society of London.

Entry written by Peter Ayres.

Marian Farquharson realised that women must be able to become full members of those many scientific societies from which at the time they were excluded. Her greatest battle was with the Linnean Society, the oldest extant natural history society in the world. Ultimately, she won the argument but she was never able to enjoy the fruits of her victory.

Marian Sarah Ridley was born on 2nd July 1846 at West Meon, Hampshire, where her father was the vicar of St Thomas’ church in the parish of East Woodhay. Her grandfather was the 2nd Baronet Ridley and she was distantly related by marriage to Ishbel Hamilton-Gordon (Lady Aberdeen). Always proud, and some said arrogant, Marian also drew strength from knowing that she was a descendent of Bishop Nicholas Ridley, the Protestant Martyr. In later life, the subjects of her letters to Aberdeen newspapers ranged from opinions on free trade to those on baptismal regeneration and the historical Christ.

Ill health, which dogged her throughout her life, forced the young Marian to give up studying music in London. She returned home and, maybe attempting to improve her health, took up field botany, in 1881, publishing, A Pocket Guide to British Ferns. Although acknowledging help from two members of the Linnean Society’s staff, she wrote that her studies would have been aided if she had been allowed direct access to the archives of the Society.

Two years later, at age 37, she married the 60-year old Robert Francis Ogilvie Farquharson, a father of two and laird of the 4,500 acre Haughton estate at Alford, 25 miles north-west of Aberdeen. He was Deputy Lord Lieutenant of Aberdeenshire. It is not known how the couple met but they shared an interest in desmids (unicellular green algae that live in freshwater) and mosses, publishing papers describing those collected in the Alford region. Marian applied successfully to join the Royal Microscopical Society (though women fellows were barred from its meetings), thereafter signing herself ‘Mrs Farquharson of Haughton FRMS’. Alas, the marriage was only seven years old when Robert died from influenza. Haughton House passed to her step-daughter. Now in love with

Scotland, Marian moved to Meigle, Perthshire , and then to the large Italianate ‘Tillydrine House’ overlooking the river Dee and Grampian mountains.

With mounting ill health limiting her travelling, it was from a distance that Marian began her fight with the London-based, male-dominated, scientific establishment. By 1899 she was not only submitting a paper supporting the right of women to join scientific societies, a key resolution of Lady Warwick’s newly formed Agricultural Association for Women, but she was contributing a paper (in her absence, read for her by Lady Marjorie Gordon) on the subject of ‘Work for Women in the Biological Sciences’, to The International Congress of Women held in London in 26 June to 7 July. The President of the Congress was Lady Aberdeen.

Women were becoming more organised, less patient with their position in scientific society. In 1900, Marian petitioned both the Royal Society and the Linnean Society that suitably qualified women should be eligible for election for full fellowship, with no restriction on their attendance at meetings. The Royal Society consulted its lawyers and then refused her petition (it was not until 1945 that it admitted its first female fellows). The Linnean Society stalled, citing a series of procedural objections and requiring a re-submission of her petition. After two years of hard argument and lobbying, Marian achieved her goal. Opposition crumbled and The Linnean agreed revise its Charter, henceforward offering full fellowship to suitably qualified women.

Many of the male members had, however, formed a dislike of Marian. Thus, when the first group of women applied for fellowship, fifteen were admitted and Marian alone was blackballed. This was in spite of her Certificate of Recommendation being signed by the eminent politician/scientists Lords Avebury and Ripon, and the eminent academic scientists, Michael Foster, Joseph Reynolds Green, and William Carmichael McIntosh (Professor of Natural History at St. Andrews University, and a personal friend).

Marian’s name was far from popular with many male members of The Linnean, and even with some of the new elected women Fellows who had benefitted from her efforts (an exception was the geologist Maria Ogilvie Gordon, see elsewhere on this site). However, her case was finally reviewed in 1908 and she was offered a Fellowship. Her fragile health had unfortunately deteriorated further. Twice she had to ask the Linnean’s Council to postpone the date when she might attend a meeting at which she could sign the Declaration that would formalise her fellowship. She visited Nice in the hope that its gentler Mediterranean climate would restore her health. Sadly, it did not. Brave, fearless and, probably, overbearing, the women’s champion died there on 20 April 1912, a fellowship of the Linnean Society having eluded her.

Marian is buried in the Farquharson family enclosure at Alford, close to Robert and to his first wife, Sarah.

The Linnean was not the first scientific society to admit female fellows but, thanks to its prestige, its decision set an example that others were encouraged to follow.

Further Reading

Ayres, PG. 2020. Women and the Natural Sciences in Edwardian Britain. In Search of Fellowship. London: Palgrave MacMillan.

Ayres, PG. 2020. Women and the Natural Sciences in Edwardian Britain. In Search of Fellowship. London: Palgrave MacMillan.

Ayres, PG. 2022. Marian Farquharson and the Struggle for the Admission of Women Fellows. The Linnean: Special Issue No. 10. The Linnean Society of London.

Entry written by Peter Ayres.