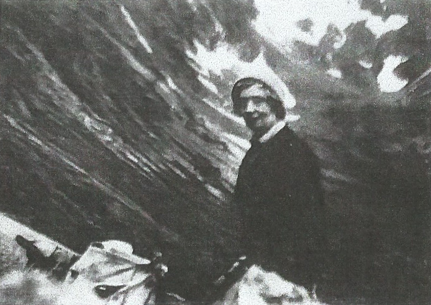

MARY McCALLUM WEBSTER (1906-1985)

Self-taught Mary McCallum Webster became a leading field botanist in the British Isles. Her ‘Flora of Moray, Nairn and East Inverness’ was published by Aberdeen University Press in 1978, the culmination of some 50 years of field work and painstaking research. A masterwork, sadly she died while compiling a similar volume for Banffshire.

Happiest in the species rich 7,700-acre Culbin forest, her favourite plant the rare one-flowered wintergreen, Mary moved permanently to Moray in the mid 1960s, settling in Dyke, home for the rest of her life. Her unique growing scheme at Rose cottage, botanical treasures, common weeds, massed gentians and cabbages hugger-mugger amongst the flowers, is no more, but a pretty garden in the village benefits still from her past advice and gifts of plants.

Mary was a remarkable woman o’ pairts. Born in Sussex to Scottish parents - her father of Old Meldrum, her paternal grandmother a profound influence - wild flowers captivated her from an early age. Educated by governesses at home until fifteen, she eventually fulfilled her wish to go to boarding school, ‘to play games and wear a gym tunic’, before being ‘finished’ in Brussels.

She was a distinguished tennis player, winning the North of Scotland Ladies Singles four times in a row in the early 1950s, getting to keep outright the Championship trophy that took pride of place on her mantelpiece. A doughty competitor into her seventies, acid comments were uttered when presented with a drop-shot she could no longer run down; while Wimbledon fortnight was one of the few occasions that found her glued to a television.

A good photographer, and artist, her cottage was festooned with bunches of dried flowers used to make Royal Highland Show first prize winning pictures; and flower arrangements on driftwood collected on the beaches of the south Moray Firth, sold for charity.

When World War Two was declared, Mary joined the Auxiliary Territorial Service, learning to cook, then training others, reaching the rank of Major; and afterwards applied her considerable skills in up-market hotels or for private clients. But botany was her life-long passion. She soon restricted employment to the winter months in order to free up the rest of the year; and by the early ‘50s was active in the Botanical Society of the British Isles (BSBI) mapping scheme for the Atlas of British Flora, over several summers covering many a mile to record plants.

In 1958, on a visit to her brother in southern Africa, she met CE Hubbard, Keeper of Graminae at Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, a friendship that triggered Mary’s keen interest in grasses, a seven-month collecting safari, then three winters in London helping to identify the 5,000 species found.

Her prowess led on to four winters at the Botany School in Cambridge, where she was something of a taskmaster, her own day a highly productive one, starting at 8.30am and ending at 10pm. An important job was to sort out Charles Darwin’s plant specimens from the Galapagos, later commenting that his notes were hard to decipher, being cross-written in two directions, on scraps of paper, and in poor handwriting.

Mary began to document the flora of NE Scotland, spending hours in the field, complete with woolly hat and boots, and carrying a card, pencil and polybag of ‘doubtfuls’. To accompany her was taxing, eyes always on the ground, not missing a thing; and her knowledge prodigious, but generously given, although she did not suffer fools gladly. Legend has it she took visitors on a circuitous route to view any rarity, so that they would be unable to find it again.

Recognition and honours came; Mary was elected a fellow of the Botanical Society of Edinburgh, and the Linnaean Society of London. And she devoted much time to national and local groups, as a BSBI council member and recorder, a faithful adherent of the Wild Flower Society from childhood, and a supporter of the revived Moray Field Club.

Although one of the First World War generation of women who never married, Mary lived life to the full, always giving her all. Renowned for her hospitality, one Hogmanay, allegedly, she threw the cork of a newly opened bottle of whisky out of the window, remarking ‘we won’t need that again’.

Mary left various dried specimens, now divided between herbaria in Aberdeen, Edinburgh and Cambridge. But, undoubtedly, her outstanding contribution to botany and science is her Flora. This 606-page volume, partly funded by her life savings, ‘sold like hot cakes’, allowing her to make two later years’ visits to Western Australia, which she took great delight in exploring. On her death, her ashes were scattered in Culbin, the location marked by a memorial of Moray sandstone.

Mary Byatt, her biographer in the book ‘Women of Moray’, sums her up well. ‘Lady Mary of Moray’, through a love of plants, gained an intimate knowledge of wild places, and cared for them deeply. She was a one-off: enthusiastic, steadfast, often stubborn, with a zest for knowledge. Direct speaking and with botanical exactitude, she also had gruff warmth and an ever-open door.

Entry written by Gordon Scott, Friends of the Falconer Museum, Forres, Moray

I am indebted to Mary Byatt, biographer, and storyteller on our Culbin forest walk in the footsteps of McCallum Webster for the 2022 Moray Walking & Outdoor Festival; also Alan Stewart, son of Olga Stewart, McCallum Webster’s principal illustrator.

The walk was inspired by 8 keystone portrait-masks, mainly of eminent scientists of the mid-Victorian period, on the Museum building’s exterior - all men.

Happiest in the species rich 7,700-acre Culbin forest, her favourite plant the rare one-flowered wintergreen, Mary moved permanently to Moray in the mid 1960s, settling in Dyke, home for the rest of her life. Her unique growing scheme at Rose cottage, botanical treasures, common weeds, massed gentians and cabbages hugger-mugger amongst the flowers, is no more, but a pretty garden in the village benefits still from her past advice and gifts of plants.

Mary was a remarkable woman o’ pairts. Born in Sussex to Scottish parents - her father of Old Meldrum, her paternal grandmother a profound influence - wild flowers captivated her from an early age. Educated by governesses at home until fifteen, she eventually fulfilled her wish to go to boarding school, ‘to play games and wear a gym tunic’, before being ‘finished’ in Brussels.

She was a distinguished tennis player, winning the North of Scotland Ladies Singles four times in a row in the early 1950s, getting to keep outright the Championship trophy that took pride of place on her mantelpiece. A doughty competitor into her seventies, acid comments were uttered when presented with a drop-shot she could no longer run down; while Wimbledon fortnight was one of the few occasions that found her glued to a television.

A good photographer, and artist, her cottage was festooned with bunches of dried flowers used to make Royal Highland Show first prize winning pictures; and flower arrangements on driftwood collected on the beaches of the south Moray Firth, sold for charity.

When World War Two was declared, Mary joined the Auxiliary Territorial Service, learning to cook, then training others, reaching the rank of Major; and afterwards applied her considerable skills in up-market hotels or for private clients. But botany was her life-long passion. She soon restricted employment to the winter months in order to free up the rest of the year; and by the early ‘50s was active in the Botanical Society of the British Isles (BSBI) mapping scheme for the Atlas of British Flora, over several summers covering many a mile to record plants.

In 1958, on a visit to her brother in southern Africa, she met CE Hubbard, Keeper of Graminae at Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, a friendship that triggered Mary’s keen interest in grasses, a seven-month collecting safari, then three winters in London helping to identify the 5,000 species found.

Her prowess led on to four winters at the Botany School in Cambridge, where she was something of a taskmaster, her own day a highly productive one, starting at 8.30am and ending at 10pm. An important job was to sort out Charles Darwin’s plant specimens from the Galapagos, later commenting that his notes were hard to decipher, being cross-written in two directions, on scraps of paper, and in poor handwriting.

Mary began to document the flora of NE Scotland, spending hours in the field, complete with woolly hat and boots, and carrying a card, pencil and polybag of ‘doubtfuls’. To accompany her was taxing, eyes always on the ground, not missing a thing; and her knowledge prodigious, but generously given, although she did not suffer fools gladly. Legend has it she took visitors on a circuitous route to view any rarity, so that they would be unable to find it again.

Recognition and honours came; Mary was elected a fellow of the Botanical Society of Edinburgh, and the Linnaean Society of London. And she devoted much time to national and local groups, as a BSBI council member and recorder, a faithful adherent of the Wild Flower Society from childhood, and a supporter of the revived Moray Field Club.

Although one of the First World War generation of women who never married, Mary lived life to the full, always giving her all. Renowned for her hospitality, one Hogmanay, allegedly, she threw the cork of a newly opened bottle of whisky out of the window, remarking ‘we won’t need that again’.

Mary left various dried specimens, now divided between herbaria in Aberdeen, Edinburgh and Cambridge. But, undoubtedly, her outstanding contribution to botany and science is her Flora. This 606-page volume, partly funded by her life savings, ‘sold like hot cakes’, allowing her to make two later years’ visits to Western Australia, which she took great delight in exploring. On her death, her ashes were scattered in Culbin, the location marked by a memorial of Moray sandstone.

Mary Byatt, her biographer in the book ‘Women of Moray’, sums her up well. ‘Lady Mary of Moray’, through a love of plants, gained an intimate knowledge of wild places, and cared for them deeply. She was a one-off: enthusiastic, steadfast, often stubborn, with a zest for knowledge. Direct speaking and with botanical exactitude, she also had gruff warmth and an ever-open door.

Entry written by Gordon Scott, Friends of the Falconer Museum, Forres, Moray

I am indebted to Mary Byatt, biographer, and storyteller on our Culbin forest walk in the footsteps of McCallum Webster for the 2022 Moray Walking & Outdoor Festival; also Alan Stewart, son of Olga Stewart, McCallum Webster’s principal illustrator.

The walk was inspired by 8 keystone portrait-masks, mainly of eminent scientists of the mid-Victorian period, on the Museum building’s exterior - all men.